- 1 read

U.S. consumers pay much less for their energy, per kilowatt, than consumers in most industrialized nations. Yet electricity and fuel prices typically fail to reflect the full cost of energy production and consumption, especially in terms of health effects.

The U.S. Congress requested a clarification of "hidden" energy costs as part of its 2005 energy bill. The result, released on Monday, concluded that the external effects of burning fossil fuels cost the United States more than $120 billion in 2005.

The National Research Council (NRC) study analyzed the damages from sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter caused by powering every building, factory, car, and truck in the continental 48 states. It is the most comprehensive review of the effects of U.S. energy policy on human health, grain crops, timber yields, construction materials, and recreation, the study authors said.

Still, the costs from water pollution, climate change, and mercury exposure were not factored into the estimate. "Our results are rather conservative," said Maureen Cropper, vice chair of the study committee.

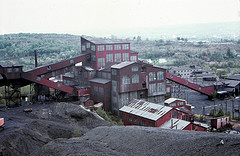

Coal-fired power plants are responsible for more than half of the estimated damages. Air pollution effects from burning coal for electricity costs U.S. residents, on average, an additional 3.2 cents for every kilowatt-hour of energy produced, although a plant's size, age, and technology, as well as the sulfur content of its coal, determine its regional health impact.

Pennsylvania residents pay average electricity prices for the United States and rely on coal for nearly half of their electricity. As a result, the state ranks second in sulfur dioxide emissions and fifth in nitrogen oxide emissions. Based on the NRC study, electricity prices in the state are an estimated 35 percent greater when health costs are included.

Motor vehicles contribute about 47 percent of the study's estimated damages nationwide. Depending on the fuel source and technology, the added cost ranges from 1.2 to 1.7 cents per vehicle mile. After measuring the damages associated with fuel extraction, production, and distribution, as well as vehicle manufacturing, the study team was surprised to find that vehicle operation accounts for less than one-third of total health costs associated with motor vehicles.

"There are a lot of damages associated with vehicle manufacturing," said Cropper, an environmental economist at the University of Maryland in College Park. "People don't think about these lifecycle emissions. They focus on what's coming out of the tailpipe."

Natural gas-powered heat and electricity cause the remaining damages. Gas-fueled plants produce, on average, 0.11 cents of additional damages per kilowatt-hour. Heating buildings and industrial processes with natural gas costs an additional 11 cents per thousand cubic feet, the study said.

The study did not quantify damages associated with nuclear energy, which supplies 20 percent of U.S. electricity, noting that expensive risk assessment and spent-fuel transportation models would have been necessary. The study committee noted, however, that although direct health damages of nuclear are "quite low," uranium mining activities have threatened nearby communities with radon exposure. Potential risks are borne mostly by uranium-exporting countries such as Australia, Canada, Kazakhstan, Namibia, and Niger.

Renewable energy sources such as wind and solar energy do not use fuels to generate electricity, and therefore do not produce adverse health effects, the study said.

To derive the health costs of these various energy options, the committee based its modeling estimates on a $6 million price for the value of a statistical life, in 2000 dollars.

While the committee refrained from making specific estimates related to greenhouse gas emissions, public health experts fear that heat waves, tropical disease, water scarcity, malnutrition, and extreme weather will become more prevalent as climate change intensifies in the decades ahead.

"Attempting to estimate a single value for climate change damages would have been inconsistent with the dynamic and unfolding insights into climate change itself and with the extremely large uncertainties associated with effects and range of damages," the study said.

***Ben Block is a staff writer with the Worldwatch Institute. He can be reached at bblock@worldwatch.org.

This article originally appeared in Eye on Earth, Worldwatch Institute's online news service. For permission to reprint Eye on Earth content, please contact Juli Diamond at jdiamond@worldwatch.org.