Overview

The dirty business of laundry has long sought improvements over old-fashioned soap and water. The Celts washed their clothing in human urine. The launderers of ancient Rome rubbed a claylike soil known as "fuller's earth" into their stained togas. During the Renaissance, books of "secrets" circulated through Europe, offering such household stain-removal concoctions as walnuts and turpentine.

Modern dry cleaning is credited to a Frenchman, Jean-Baptiste Jolly, who in the mid-19th century realized the stain-removal potential of kerosene when his maid accidently spilled a canful onto his soiled tablecloth. Hydrocarbon-based solvents prevailed thereafter until the 1960s, when flammability concerns and the affordability of new synthetic chemicals led to a switch. Tetrachloroethylene, also known as perchloroethylene ("perc"), became the preferred solvent among most of the world's dry cleaners.

An estimated 180,000 dry cleaners worldwide are believed to use perc. More than 30,000 small- and large-scale operations are based in the United States alone. The rise of service economies in the developing world will likely increase demand for dry cleaning, although many countries are shifting toward more casual office dress codes.

Process

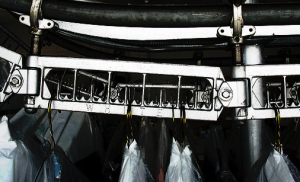

The typical dry cleaner uses a combined washing machine/clothes dryer. A rotating stainless-steel basket holds the laundry while a circulating outer shell sprays solvent throughout the clothing. The machine extracts the solvent, recovering nearly all of it for further use.

Although much of the perc is recycled during dry cleaning, some solvent inevitably evaporates into the surrounding air. The cleaning process also leaves a sludge-like byproduct that contains solvent residue, and only a relatively small portion of this is properly treated; most is mixed with other waste products and burned in incinerators and cement kilns.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies perc as a probable human carcinogen. Those who work in or live near dry cleaning facilities are exposed to various cancer risks, according to the World Health Organization, including bladder, throat, and lung cancer. Damage to the liver, kidneys, nervous system, and memory is a threat as well, according to the U.S. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health.

Perc pollution contributes to the formation of smog. The toxin can also accumulate in water resources; U.S. Geological Survey hydrologists have detected perc at measurable concentrations in nearly 1 in 10 tested wells drawing on major aquifers across the country.

Mitigation and Alternatives

Advances in dry cleaning machinery have led dry cleaners in the United States to cut their solvent use by 80 percent in the past decade, according to the Dry Cleaning and Laundry Institute. Still, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that the country's dry cleaners released some 10,000 tons of perc in 2006.

The European Union, Australia, and Canada have implemented regulations to further limit perc releases and minimize its use. California has passed the only perc phase-out, requiring that dry cleaners transition to alternatives by 2023, but many large dry cleaners have avoided regulation by moving their operations to Mexico.

About half of garments dry-cleaned with perc may instead be cleaned with a process known as "wet cleaning." The technique combines old methods (biodegradable soap and water) with new technologies such as computer-controlled dryers and stretching machines. Another alternative, immersion in liquid carbon dioxide (CO2), has been commercially available for the past decade. The Union of Concerned Scientists considers the process beneficial to the climate: The CO2 is nearly all recaptured, and it requires less energy than traditional dry cleaning.

Consumers seeking alternatives can also remove many stains with household substances such as baking soda, hydrogen peroxide, or cornstarch.

Ben Block is a staff writer with the Worldwatch Institute. He can be reached at bblock@worldwatch.org.

This article originally appeared in Eye on Earth, Worldwatch Institute's online news service. For permission to republish this article, please contact Juli Diamond at jdiamond@worldwatch.org.

The dirty business of laundry has long sought improvements over old-fashioned soap and water. The Celts washed their clothing in human urine. The launderers of ancient Rome rubbed a claylike soil known as "fuller's earth" into their stained togas. During the Renaissance, books of "secrets" circulated through Europe, offering such household stain-removal concoctions as walnuts and turpentine.

Modern dry cleaning is credited to a Frenchman, Jean-Baptiste Jolly, who in the mid-19th century realized the stain-removal potential of kerosene when his maid accidently spilled a canful onto his soiled tablecloth. Hydrocarbon-based solvents prevailed thereafter until the 1960s, when flammability concerns and the affordability of new synthetic chemicals led to a switch. Tetrachloroethylene, also known as perchloroethylene ("perc"), became the preferred solvent among most of the world's dry cleaners.

An estimated 180,000 dry cleaners worldwide are believed to use perc. More than 30,000 small- and large-scale operations are based in the United States alone. The rise of service economies in the developing world will likely increase demand for dry cleaning, although many countries are shifting toward more casual office dress codes.

Process

The typical dry cleaner uses a combined washing machine/clothes dryer. A rotating stainless-steel basket holds the laundry while a circulating outer shell sprays solvent throughout the clothing. The machine extracts the solvent, recovering nearly all of it for further use.

Although much of the perc is recycled during dry cleaning, some solvent inevitably evaporates into the surrounding air. The cleaning process also leaves a sludge-like byproduct that contains solvent residue, and only a relatively small portion of this is properly treated; most is mixed with other waste products and burned in incinerators and cement kilns.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies perc as a probable human carcinogen. Those who work in or live near dry cleaning facilities are exposed to various cancer risks, according to the World Health Organization, including bladder, throat, and lung cancer. Damage to the liver, kidneys, nervous system, and memory is a threat as well, according to the U.S. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health.

Perc pollution contributes to the formation of smog. The toxin can also accumulate in water resources; U.S. Geological Survey hydrologists have detected perc at measurable concentrations in nearly 1 in 10 tested wells drawing on major aquifers across the country.

Mitigation and Alternatives

Advances in dry cleaning machinery have led dry cleaners in the United States to cut their solvent use by 80 percent in the past decade, according to the Dry Cleaning and Laundry Institute. Still, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that the country's dry cleaners released some 10,000 tons of perc in 2006.

The European Union, Australia, and Canada have implemented regulations to further limit perc releases and minimize its use. California has passed the only perc phase-out, requiring that dry cleaners transition to alternatives by 2023, but many large dry cleaners have avoided regulation by moving their operations to Mexico.

About half of garments dry-cleaned with perc may instead be cleaned with a process known as "wet cleaning." The technique combines old methods (biodegradable soap and water) with new technologies such as computer-controlled dryers and stretching machines. Another alternative, immersion in liquid carbon dioxide (CO2), has been commercially available for the past decade. The Union of Concerned Scientists considers the process beneficial to the climate: The CO2 is nearly all recaptured, and it requires less energy than traditional dry cleaning.

Consumers seeking alternatives can also remove many stains with household substances such as baking soda, hydrogen peroxide, or cornstarch.

Ben Block is a staff writer with the Worldwatch Institute. He can be reached at bblock@worldwatch.org.

This article originally appeared in Eye on Earth, Worldwatch Institute's online news service. For permission to republish this article, please contact Juli Diamond at jdiamond@worldwatch.org.